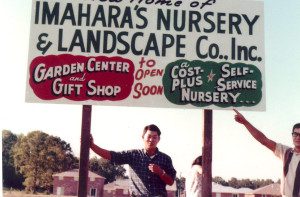

Paradise found: Walter Imahara continues his family legacy

This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of inRegister.

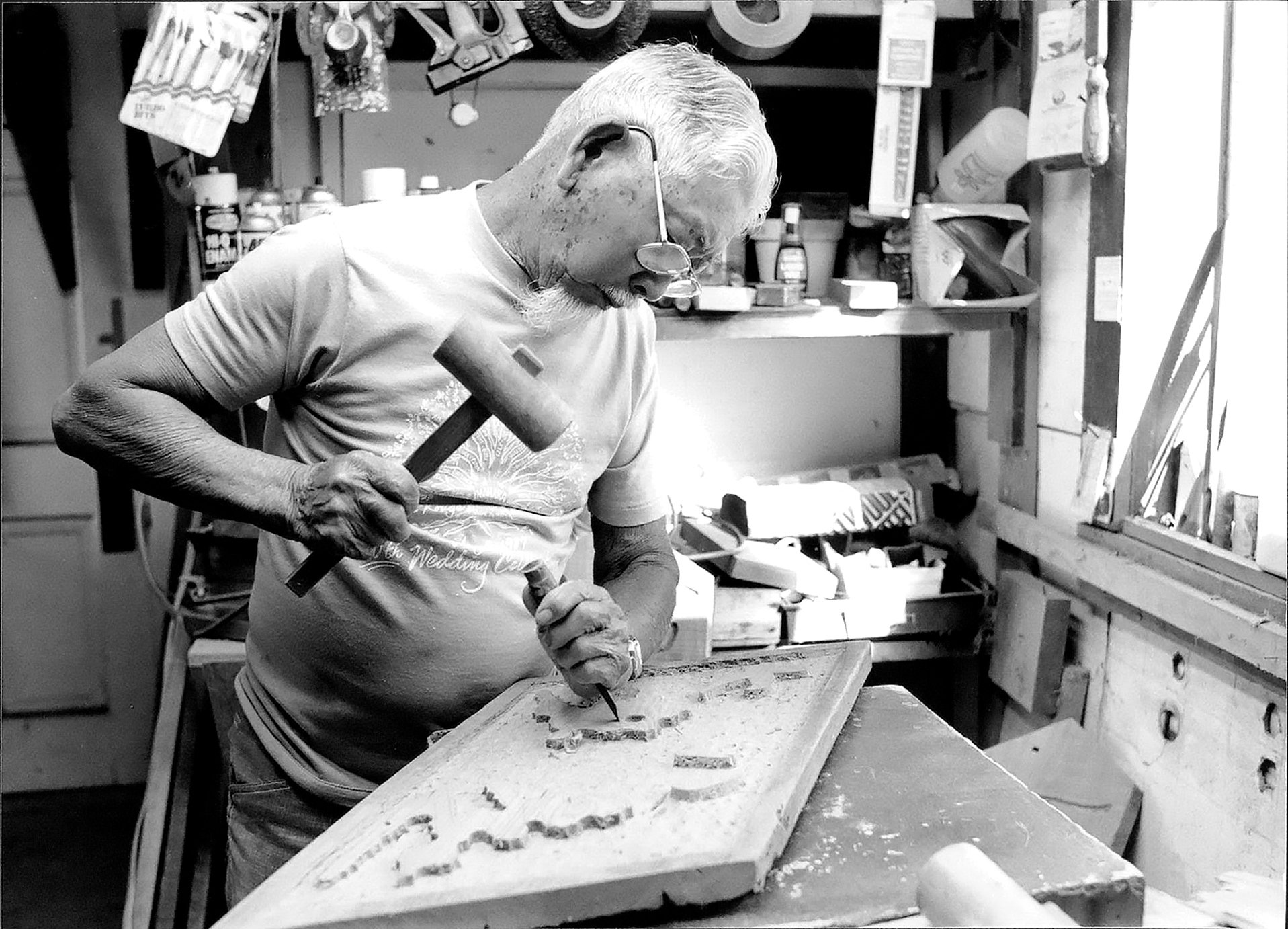

Walter Imahara, the now-retired spearhead of Imahara’s Landscape Company in Baton Rouge, will tell anyone the story of his family. Those who wander past the gates of his enormous botanical garden in St. Francisville are first guided to a room that features a wall filled with Japanese haiku poems carved onto cypress blocks by Walter’s father, James Imahara. Guests are encouraged to view the family albums on display before they proceed to the botanical garden.

There’s a reason why the Imahara family history room is the first stop on the garden tour: One would not exist without the other.

Watering the roots

Sitting on 54 acres of once-inhospitable land near Bayou Sara, the garden is Walter’s family legacy and the culmination of his lifelong passions. Every part of it means something to him, from the poodle-like topiary at the front of the garden to each of the nine ponds the garden now contains.

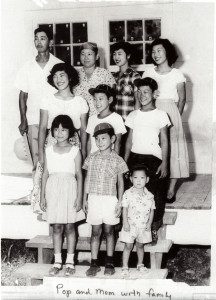

“Each pond is for each child of my parents,” Walter says. “Each pond has different aspects that correspond to each of us.”

The ponds cascade down a ridge at different levels, and there are two more ponds planned for his parents. These ponds will connect to each other and the overflow will drain into an eroded area, then into the Mississippi River, and ultimately, into the Gulf of Mexico.

“Back to the foundation,” Walter says.

Some 3,000 azaleas, 25 varieties of crape myrtle (including some imported from Israel), holly groves, dogwoods, weeping trees, palms, magnolias and countless other plants, rooted in groups of threes and fives, grace this massive labor of love. There’s even a tiny “Mount Fuji” on the property that serves as a lookout point. Not bad for a retiree.

“Walter is a ‘big picture’ kind of guy,” his niece, Wanda Chase, explains. She is now the third generation to own Imahara’s Landscape Company in Baton Rouge. “His notion of retirement was not to stop working, but to start a new adventure.”

A living legacy

The Imahara family history is heavy to a degree that only the unluckiest of Americans can understand. Walter’s father, James, was a California-born nisei, or second-generation Japanese immigrant to North America. By 1940, the nisei Imaharas had carved out a niche for themselves in California. Their orchard helped provide for their growing family, and during those years James helped new Japanese immigrants learn to read and write English; the latter would earn him recognition from the Emperor of Japan many years later.

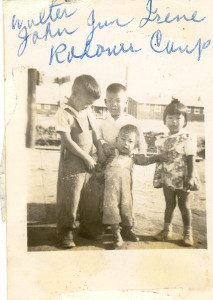

But long before receiving that honor, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and the Imaharas were faced with one of the darker parts of American history. They reported to a wartime internment camp a few months after the bombing, and outside of a few duffel bags, they had to leave their property and possessions behind. They were stripped of their identities and given numbered tags to wear. Over the length of the war, the family was shuffled around to a few camps before landing far from home in Rohwer, Arkansas, where the eighth Imahara child was born behind barbed wire.

Walter was 4 years old.

“We tell people now, we had fun at the camps,” he says, unflinching. “We played baseball. We played games.”

By the time the family was allowed to leave the camp in Arkansas, James Imahara was in his late 30s. His California orchard was never returned to him, and faced with the incredible task of starting over with nothing, he took the government’s complimentary train tickets and moved his family of 10 to New Orleans, where he took a job as a landscaper for a plantation. He was, by all accounts, aggrieved by the experience.

“He was very bitter about it,” says Walter. “[But] it didn’t stay with him for too, too long.”

By the time the family moved to Baton Rouge, not only had his father put the bitterness behind him, but he made it clear to all his sons that they would serve their country in the armed forces.

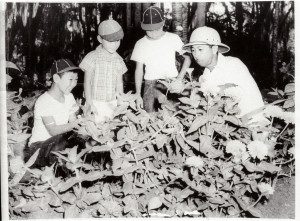

In Baton Rouge, James started a business called James’ Gardening Service and worked tirelessly to pay tuition for all nine of his children. The children helped, too. Wanda Chase, who now owns the family business, still serves customers who remember those early days.

“I have clients who recall Grandpa and Grandma arriving in the early morning with a load of kids in the back of a pickup truck,” Wanda says. “They would work all day plugging grass, stopping to have lunch as a family.”

Walter remembers his father as a man on a mission, who held his children to a high standard. Walter’s sisters were urged to earn college degrees at a time in America when women weren’t often pointed in that direction.

“He told all of his kids to get an education, because nobody can take that away from you,” Walter says. “Then you serve your country. Then you buy land.”

Toward the end of his life, James Imahara took up carving original haiku onto wooden cypress blocks. The Imaharas see it as his legacy. Wanda refers to Walter’s botanical garden as a legacy, much like her grandfather’s haiku boards.

“Grandpa did it with his haiku Japanese wood carvings, Walter did it with his legacy garden,” Wanda says. “The ability to make a difference lies within each of us.”

“Grandpa did it with his haiku Japanese wood carvings, Walter did it with his legacy garden,” Wanda says. “The ability to make a difference lies within each of us.”

Plant a tree

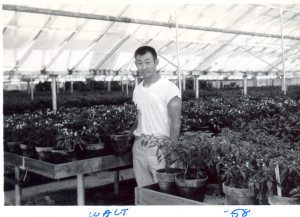

You gotta have a dream, Walter likes to say. “I had the landscaping business, and you gotta have a dream, you know? My dream was to have a beautiful garden.”

The botanical garden on Mahoney Road is a celebration of a particular moment in the Imahara family history—the part where the progeny blooms into everything their elders worked so hard for.

“Walter has always been about giving back to those who have helped him along the way,” Wanda says. “One of his favorite sayings is, ‘If you want to have happiness for today, go for a nice dinner out. If you want to have happiness tomorrow, go on a cruise. If you want to have happiness for the future, plant a tree.’”

Though he has planted a great many trees for future happiness, Walter still loves to try out new plants. Back in the early 1970s, he introduced a new iris variety to Louisiana, called the Louisiana Walking Iris, which became a local favorite.

The garden is no small feat, and Walter spares no expense with its maintenance. He had intended it to be a gift to Baton Rouge for the many years of support, but he had to begin charging admission to keep costs down. Walter and his wife Sumi have no children, so he has accepted the idea of turning the garden over to a foundation.

“I would be okay with taking my name off the ownership, but I would still like to work in the garden,” Walter says.

Before that takes place, he has to tie up a few loose ends, including the acquisition of one last piece of his family history: an Imahara family monument that currently sits in Hiroshima. Public interest in the monument has waned over the years—Walter says it’s because there are no more Imaharas in Hiroshima. “In Japan, when there is no more public interest in something, they tear it down,” Walter says. “That’s the Japanese way.”

When he visited the city some years ago, he couldn’t bear the thought of the monument being destroyed, so he began to figure out a way to bring it to his garden. By the end of 2016, it will be placed in what Walter refers to as “Mom and Pop’s garden,” the traditional Japanese area of the garden. Then, he imagines, the garden will be finished—for now, anyway.

Imahara’s Botanical Garden is open on weekends in March through July, October and November, and both group and self-guided tours are available. For details, call 635-6001 or see imaharasbotanicalgarden.blogspot.com.