Faces of the Southern past fill the home of a passionate collector and his family

Sunlight streams through a glass roof into the courtyard of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American Wing, casting long shadows behind marble statues and building anticipation of what lies behind the façade of a former Wall Street bank building now embedded in this New York City cultural institution. Within the galleries off this grand space are some of the most recognizable images in American art, from John Singer Sargent’s mysterious Portrait of Madame X to the 12-by-21-foot canvas of Washington Crossing the Delaware.

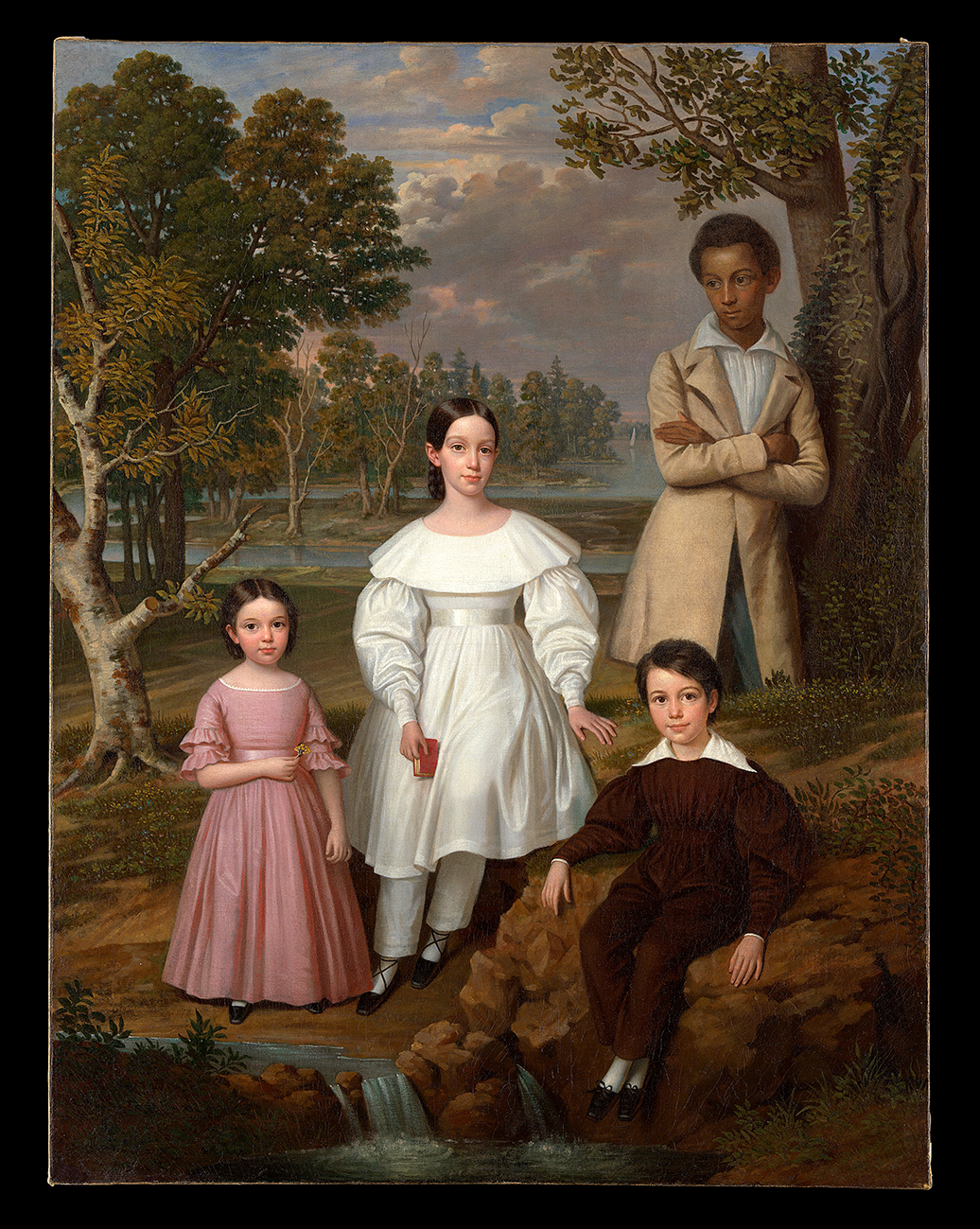

Beginning this fall, another American face—less well known but equally unforgettable—will also be displayed on these hallowed walls. As a recent New York Times front-page headline proclaimed, “His name was Bélizaire.”

Were it not for years of research fueled by a singular passion, this painting of an enslaved teenage boy with the children whose parents owned him would likely never have come to rest in one of the world’s most prestigious museums. But Baton Rouge art collector and historian Jeremy Simien made it a personal mission to ensure that Bélizaire’s story be told, and that mission culminated in the painting being acquired by the Met earlier this year.

“I think it’s appropriate, and I think it’s timely,” says Jeremy of the acquisition as he sits behind a desk in his Country Club of Louisiana home. Bélizaire and the Frey Children once hung on the living room wall here, where Jeremy and his wife Lindsay and their now two-year-old son Jordan could see it daily among the many other historic pieces of art Jeremy has collected over the last decade. Like Bélizaire, each of these works has its own story, and through Jeremy’s diligence and rapidly expanding social media following, these stories are being unearthed and revealed to a new generation.

Though Jeremy began collecting art and antiques in earnest in 2013, his interest in history dates back much further. “When I was about eight years old, we rented Tut: The Boy King, a documentary video with Orson Welles,” he recalls. “My mind was blown. I became obsessed with ancient Egypt for a while, buying books about it from every bookstore I went to and talking nonstop about it to my parents. It lasted for several years—to the point where I was even asking my mom to buy Egyptian cotton towels when I saw the burial mask of King Tut on the tag.”

It was around the time that Jeremy and his wife Lindsay bought their first home that Jeremy’s interest in more recent historical eras began to grow. “We began to learn about each other while trying to decorate the house,” he says. “I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was building an environment that reflected the things I appreciated. I began to recognize why these things were important to me—and, it had to do with my family history. I wanted to honor my ancestors.”

Jeremy’s interest in the material culture of Louisiana led him to seek out tangible pieces of that history—furnishings and decorative items that would have been similar to the ones he discovered on his ancestors’ inventory sheets from generations earlier. Art soon became an important part of his collecting life.

One of the first portraits he acquired was a painting of a Southern lady wrapped in an indigo-colored shawl. “At the time, I didn’t know what time period it was from, but I knew it was old,” he says. After the purchase, he learned that the original frame had been replaced, making the painting less valuable. But, he felt a connection to the portrait’s subject nonetheless, and the work still holds pride of place among the many he has since amassed.

As his collecting journey progressed, Jeremy developed a special focus on tracking down portraits of Creoles of color and returning them to Louisiana. He became a fixture at art auctions around the country, bidding by phone and celebrating his purchases and their deeper meaning. For each piece he acquired, Jeremy conducted extensive research to find out as much about the subject and the circumstances of the portrait as he could—and, for many of these portraits, he shared those findings with his Instagram followers.

“My main goal in collecting is to understand more about the world around me, how it came to be, and to find commonality and to share that with people through sharing different cultures,” he says. “I believe it was necessary at a time to say, ‘Listen, everybody, these people deserve to be seen.’”

In 2015, Jeremy first learned of the Bélizaire painting, though the boy’s name was then a mystery. As the New York Times article and others have noted, the 1837 painting had been in storage at the New Orleans Museum of Art for more than 30 years before being deaccessioned in 2005 and purchased by an art dealer who noticed an anomaly. A shadowy area in the landscape behind what seemed to be the painting’s only subjects—the three white children—turned out to be masking a Black teenager, revealed only after the painting was cleaned by a conservator. Jeremy became determined to find out more about the painting and to ensure that it came home to Louisiana.

When Jeremy wasn’t immersed in finding out more about the Bélizaire painting and its origins, he and Lindsay were busy moving into their current home in the Country Club of Louisiana. Each room became a showplace for the treasures they had discovered, and even the arrangement of the rooms was part of the plan. The living room’s mix of antique and vintage furniture from several different eras, for example, draws inspiration from Maison Chenal, the 18th-century Pointe Coupee Parish home where noted collectors Jack and Pat Holden lived out the French concept of “tout ensemble.” The Holdens’ names pop up again and again in conversation here, as Jeremy points out a pair of Old Paris porcelain pieces that were once in the Holdens’ residence in New Orleans’ Pontalba Apartments, and he recalls that he placed a phone bid for the piano that now sits in his library, while walking through one of the Holdens’ historic homes.

But the Simiens’ house is no museum, as Jeremy and Lindsay are quick to admit as they point out a footed porcelain bowl securely anchored to a living room table with museum wax. They learned the hard way to protect their priceless pieces from the wobbly and curious wanderings of a toddler. Even so, there is plenty for young Jordan to explore, especially in the Disney-themed kitchen where colorful signs inspired by some of the family’s favorite animated films sit atop cabinets and a model of the Disney World monorail encircles Cinderella’s castle on the granite-topped island.

These magical details reflect Lindsay’s job as a Disney travel agent, but Jeremy is no stranger to the House of Mouse either; he recently served as a consultant on the Haunted Mansion movie, which was directed by his second cousin Justin Simien. “They asked me to provide insight into 19th-century New Orleans culture and art,” Jeremy says of the gig. “I talked about the cultural fusion that makes New Orleans what it is.”

After six years of searching, Jeremy acquired the Bélizaire painting in 2021. Many months of additional research determined that the children were part of the Frey family of New Orleans, and that their enslaved servant Bélizaire had been painted out of the portrait sometime after the boy had been sold to another owner. Jeremy knew that the painting’s significance was even greater than he had first realized, and he shared what he had learned with followers of his Instagram account. “I didn’t market this painting—I’m not a dealer, I’m a collector,” he explains. “But once I found out about the importance of Bélizaire and his legacy, I felt this responsibility to tell the story in the right way. I wanted the painting to be somewhere that it would be safe, but not with a private collector where it couldn’t be seen.”

Meanwhile, Jeremy and Lindsay were continuing to write their own story at home by conjuring rooms as immersive as a Disney attraction. An empty guest bedroom upstairs became the perfect canvas for Jeremy to create the look of an old plaster and bousillage house as it would have looked in 1880s Louisiana. This “time capsule” space, with its walls carefully faux finished by Jeremy, contains a mix of fine antiques and more primitive and practical pieces. “I was initially inspired after reading a 1928 Scribner’s Magazine describing an old Creole cottage in Natchitoches with ‘mud walls,’ also known as bousillage,” Jeremy wrote in an Instagram post about this room makeover project. “In this small 18th-century house lived a cousin of my great-grandmother’s.”

With his own bloodline including African, Acadian, Spanish and indigenous ancestors and DNA from 24 world regions, it was only a matter of time before Jeremy would seek to widen his collecting range to include other cultures beyond the Bayou State. On this day, he is wearing a pair of Pueblo and Navajo turquoise necklaces that are part of a growing collection of Native American and indigenous art that he began a few years ago. “I have lots of early Native American squash blossom necklaces that I got from dealers in New Mexico,” he says. “Some have African beads on them. Some are museum-quality pieces and date back to the 1890s.”

Jeremy says he also finds himself drawn to the Spanish Colonial world, and he recently bought a Mexican Colonial painting from the 1790s. “I think Louisiana has largely ignored its connection to Spanish cultures, and that’s something that I think we need to explore, especially with the large Hispanic population now,” he says, noting that Spain governed the colony of Louisiana for 40 years. “We can do that through material collections.”

Noting that another Louisiana portrait had just been delivered to his doorstep the day before, Jeremy hasn’t completely moved away from his collecting roots. “It’s still important to me, but there are other parallel histories that I’m wishing to share,” he says.

Curators at the Metropolitan Museum of Art recognized the Bélizaire painting’s importance after Jeremy says others had not. Their acquisition of the painting was finalized earlier this year, marking a triumphant milestone in the artwork’s tumultuous history—and leaving Jeremy to turn his own focus to the many other artworks he has either acquired or is actively pursuing.

“From erasure to restoration—I think that resonates with a lot of people,” Jeremy says. “I’m just lucky and blessed to have been chosen to share the story. This wasn’t planned. There was no guidebook. There was no next step. But, things fell into place. I think some of that—a lot of that—was otherworldly, whether you want to call it the ancestors or God or karma. There were major forces beyond me, assisting me along this journey.”