Long Story Short: The Boiler Plate

We’ve got a good thing going in Louisiana. And there is no denying that we take it for granted. Sure, we’ve got to fight through politics, and policy and potholes and such—and those are real things that matter a whole lot—but we also have a culture that can’t be duplicated anywhere else in the country. Ever been to a Cajun restaurant outside the state? Shame on you. Ever order a Creole-style shrimp etouffee north of the Mason-Dixon? You probably got what you deserved. Ever attended a crawfish boil produced by a native Alabamian? It’ll make you cry.

Some things are better left to the professionals.

The good news is that we are surrounded by professional crawfish boilers in south Louisiana. From a young age, children are thrown into the role of outdoor kitchen staff during the spring season, surrounded by live crustaceans with claws, a tub of boiling water that must be overturned and drained, and a chef—often related to the children—who has been drinking beer since the gas burner was lit. If the young girls and boys look up long enough from letting a few pet crawfish loose (“Go free. You can make it to the ditch!”) they learn to add the potatoes and corn and how much seasoning is best according to family lore. It’s a Louisiana ritual.

In our family, we’ve turned this Louisiana ritual into a Good Friday festivity at our farm smack dab in the middle of really-super-rural Louisiana (north of Melville, which is north of Krotz Springs) and we tell the children not to get hurt or else you’ll end up getting sutured together with a bit of fishing line and a darning needle sanitized with bleach. We bring four-wheelers and ATVs and washer boards (for a spirited tournament) and volleyballs and fishing poles and an extra pair of clothes in case things get muddy. We have a homemade zip line and a tire swing. And ponds. And alligators if you look too close. But we’ve got the “Gator Man” up the road that can help us out if we need him.

(I’m not going to lie and say we haven’t caught a few alligators on our own, but this falls in the best-for-professionals category. Especially since the Gator Man bagged a 11-foot-long one on our land across the highway, close to the Atchafalaya River.)

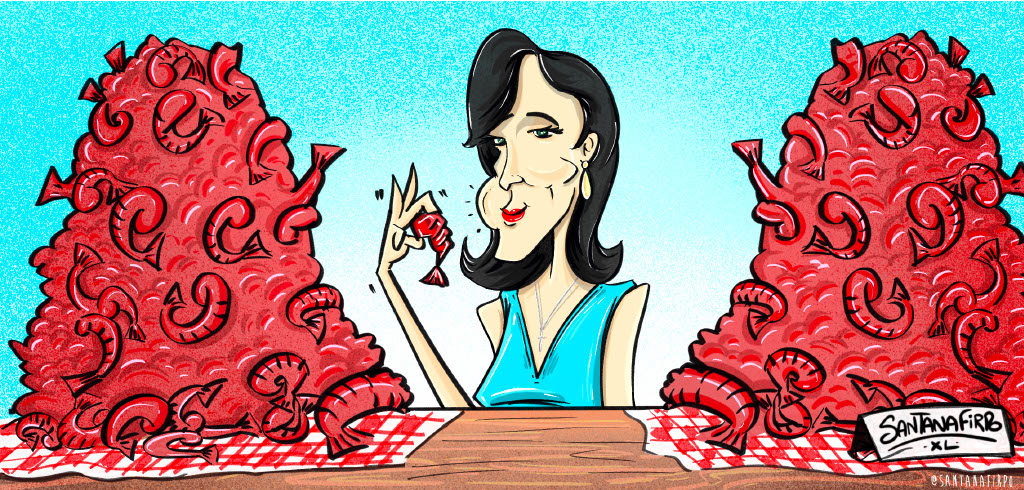

But the day’s focus is on the crawfish boil taking place during the washer-board tournament and on the crawfish’s size (this year they were perfect) and seasoning (again perfect) and amount (just right) that were cooked. After kids have sprawled out and driven off all over the farm, they round up to eat under the back porch of the camp—a come-as-you-are mélange of family and friends and tagalongs that bring the season together.

The scene is loud, filled with laughter and voices and music playing in the background. People getting up and sitting down and children running. Hands busy with the peeling and dipping and paper-towel-dabbing off of faces and fingers. Stories being told that you don’t want to miss, but you only catch pieces of because of the interruptions and the complete chaos of it all. There is something so utterly uncivilized about a crawfish boil that makes it so appealing. And we could use a bit less of civilization right about now, can’t we?

That’s what we are all thinking when the last black bag of trash is hauled away, the big pots have been cleaned and the four-wheelers have been hosed off. We sit on the back porch and watch the light fade over the vegetable garden that lines the path to the pond. We could live here, we say. In case the world is going to end, we could live off the land. We could survive out here, on the vegetables and the deer meat from the woods. Live off the grid.

We consider it for a while and are girded with the relief that we have a backup plan. A place to retreat. To hide out. To be unseen. But as the sun slowly sets behind the tree line hundreds of yards away past the sugar cane fields, we realize we need to pack up and go home. It’s time to get back to reality.

For now, we’ll leave living off the grid to the gator-catching professionals.