Since gracing the cover of inRegister’s inaugural issue, St. Francisville has grown into a must-see destination

Decades before the vibrant hub of shops, restaurants and bed and breakfasts emerged in St. Francisville, there existed only a mix of small-town essentials—Sonny’s Pizza, Rinaudo’s Hardware and Speedway Car Wash. Some of the area’s now famous historic homes sat abandoned in the woods.

In the 1970s, Arlin Dease bid on one of those homes during a sheriff’s sale, hoping to find treasures to fill his antique store. As the story goes, he found far more than furniture. Discovering the lore of The Myrtles, known today as one of America’s most haunted homes, and painstakingly restoring each room ignited his passion for historic preservation. After The Myrtles, he restored Mount Hope and then Nottoway in 1980. It’s there that the story of Hemingbough begins.

After selling the refurbished Nottoway to Sir Paul Ramsay for $4.5 million in 1985, Dease felt called to give back using the windfall from the sale. “God can humble us in many different ways,” he says, taking a pause from scribbling in his notebook. “Sometimes through upheavals and tragedies, but he can also humble us through an abundance of his love, his grace and plenty. As plainly as you and I are talking, God spoke to my heart and mind. He said, ‘Provide a place that anyone and everyone can come as they need it to experience my unconditional love and forgiveness.’”

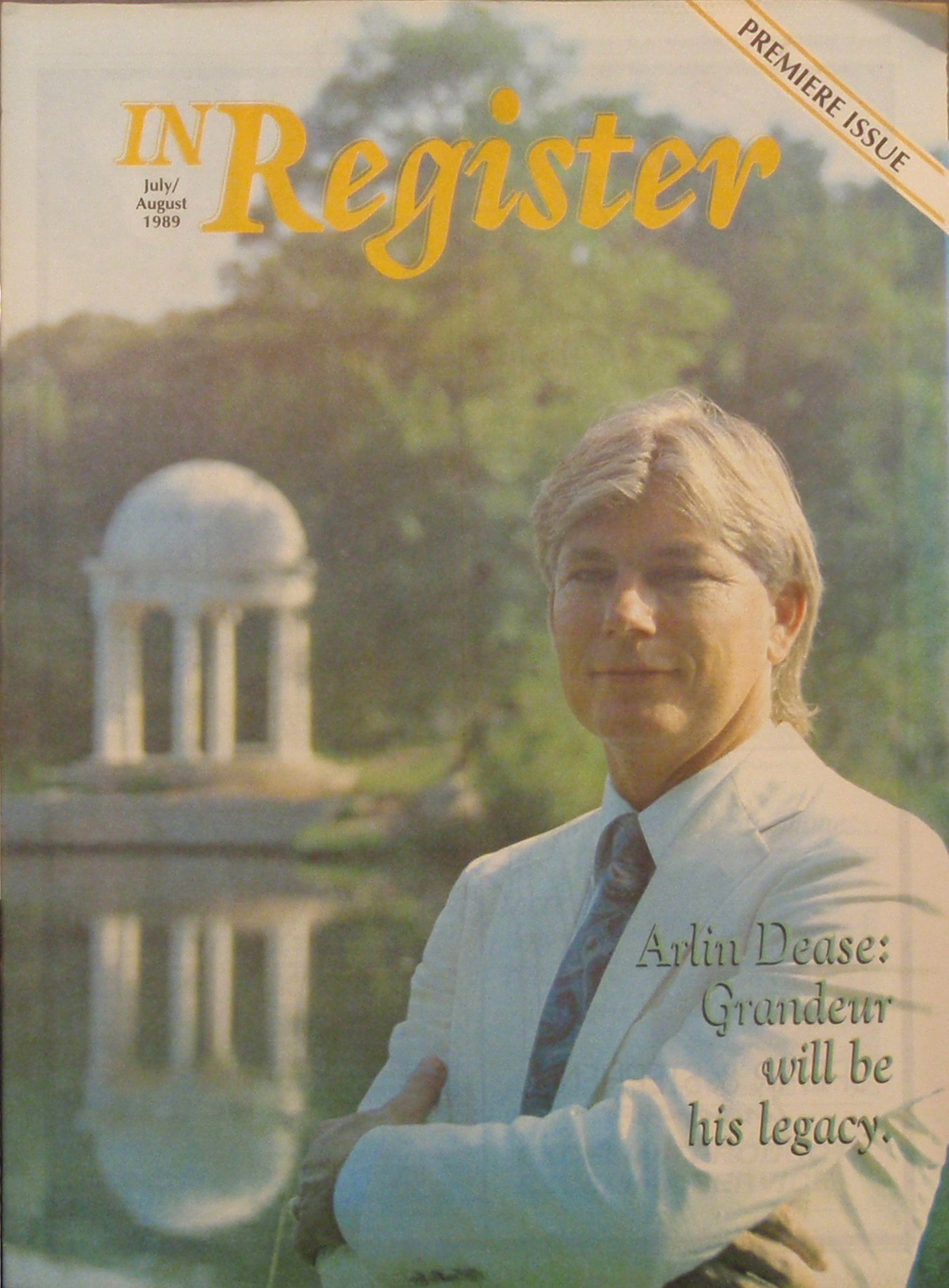

In 1987, Dease opened Hemingbough to the public. In 1989, the premiere issue of inRegister featured him and his one-of-a-kind 238-acre retreat as the cover story. Hemingbough also served as the venue for the inRegister launch party. Dease credits that coverage as the catalyst for the destination’s first boom in popularity as a wedding venue.

As guests flocked to Hemingbough for weddings, concerts and sunrise church services, they discovered far more than a venue. They discovered St. Francisville. Over the next several decades, residents and leaders carefully crafted a vision to revitalize and preserve the town’s quaint, quiet and historic allure.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified the desire for close-to-home staycations and second homes away from the hustle and bustle of bigger cities. Many found the solace they sought 22 miles past where the freeway ends, guided by rare rolling hills into “the town two miles long and two yards wide.”

“Locals know the importance of having a community that is welcoming to visitors,” explains Devan Corbello, executive director of the West Feliciana Tourism Commission. “More local entrepreneurs saw the potential St. Francisville had and began opening local shops, bed and breakfasts, and restaurants a couple of years before the pandemic, so when more people discovered us, they saw a vibrant small town. Since then, more people have invested in our community.”

People like the Charlet family, who developed North Commerce. Don and Susan Charlet started with a plan to relocate their design and home décor store, The Corbel, to St. Francisville in 2020. Soon, Don, who Susan calls “the dreamer,” began envisioning a hub of locally owned shops anchored by The Corbel. There would be space for all of that and a large-scale event venue at the former site of Rinaudo’s Hardware, which had sat vacant for 35 years. After careful collaboration with city leaders and the West Feliciana Historical Society, “we took it to the studs,” Susan Charlet says.

What was once the town hardware store and pharmacy—and before that, a cotton gin in the 1930s—is now a hub of locally-owned shops known as North Commerce. Since 2022, The Corbel, Barlow Fashion, Deyo Supply Company, Hotel Toussaint, Big River Pizza Co. and the 12,000 square-foot event venue The Mallory, named after the couple’s daughter, have opened. This fall, Bayou Sara Brewery is slated to open as the final piece of North Commerce, Susan says. The brewery’s name is a nod to the lost river town destroyed by fires, floods, and a shifting bayou, whose houses were moved on carts to what is now St. Francisville.

“We knew we wanted it to become an experience,” Susan Charlet says of North Commerce. “You can come and hang out, stay the night, eat and drink.”

St. Francisville has evolved into one of Louisiana’s best-known secrets with buzzing festivals, unique outdoor recreation, historic sites, fine dining and boutique accommodations. “Visitors come to us to escape a busy city and relax in a quintessential southern small town,” Corbello says. “It is not a ‘sleepy’ small town like one would expect. It is lively and filled with things to do throughout the year.”

Even among the buzz of festivals and grand openings, many homes and historic sites look nearly identical to how they did 300 years ago thanks to careful restoration. And the place where time seems to stand still remains the same, too.

“Has Hemingbough changed in 37 years?” Dease repeats, smoothing the white tablecloth on one of the many tables set up for that evening’s wedding. “Not a bit,” he smiles. “In 37 years, not one person has ever paid a single penny to visit these grounds. That means a lot to me.”

The sprawling acreage is as serene as that day of the inRegister cover story photo shoot in 1989. “Nestled in the rolling hills of the Felicianas, Hemingbough stands like an opulent setting from days gone by,” the article reads, those words still ringing true.

Now, Dease is working on the next development for Hemingbough, a new type of preservation project for him. He plans to build an “assisted as you need it” living facility and neighborhood so that the folks who remember the early days of Sonny’s Pizza, Rinaudo’s Hardware and the Speedway Car Wash have a quiet place to age gracefully.