Off the Page: The Katrina Decade

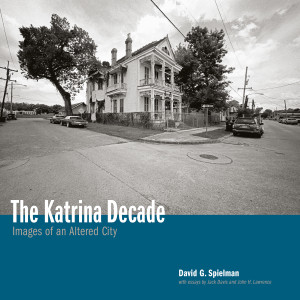

Photo by David G. Spielman. Courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Remove the glossy dust jacket, and the title on the bound cover of David G. Spielman’s The Katrina Decade: Images of an Altered City is almost imperceptible. Printed in transparent ink on a muted gray background, it’s easy to miss the small text—unless a curious reader is looking from just the right angle, with the light hitting the surface in just the right way.

This subtle detail is a striking analogy for the photographer’s work featured within. Weathered roofs wear wigs of thick vines. Paint peels away from a theater’s ornate plasterwork. These are things that might not have been noticed except by someone looking at them from just the right vantage point, with the perspective of a longtime New Orleans resident who knows these streets like no stranger does.

“I see ripples of change that an outsider would miss, in places an outsider doesn’t know to visit,” explains Spielman in the book’s foreword. So with his Leica camera hanging around his neck, Spielman has spent the 10 years since the hurricane quietly capturing what he calls a “contradiction of rebirth and blight.”

In stark black and white, the photographer seeks to memorialize the parts of post-Katrina New Orleans that the national media glosses over. Rather than focusing on a bustling Bourbon Street, he aims at a lone city bus moving down a New Orleans East road surrounded by overgrown lots. He steps inside an abandoned gym in Press Park to find the floor strewn with debris and every vertical surface—including backboards—covered with graffiti.

Spielman drew inspiration from the Works Progress Administration photographers of the 1930s who captured a nation climbing out of the Great Depression. “Fifty or 100 years from now, people will want to see what New Orleans was like after Hurricane Katrina,” he writes.

Many of the photos paint a bleak portrait of a city still waiting for rescue. “Outside what may be considered a penumbra of privilege, work still needs to be done,” writes photographic historian John H. Lawrence. “And if the photographs seem cold and sad rather than warm and happy, it is because the task of rebuilding is incomplete.”

But hope is also present—if you look, as Spielman has, from just the right angle. Shown here are the faces of the resilient—the nuns of St. Clare’s Monastery, a Gert Town inhabitant smiling from a window, a musician playing his sousaphone on a Central City front porch.

“Our digital world puts so many images before our eyes, in such quick succession, that we miss the opportunity to slow down and reflect on what has happened, what is happening, to New Orleans,” Spielman writes. “I needed and wanted to capture these scenes that look so static but that are in fact constantly changing, and I wanted to document the city’s intangible commodity of perseverance.”